If you follow white collar crime stories you may notice a pattern: Most investigators talk about fraud, but very few can actually prove it with documents alone.

Sam Antar can. He has an almost unnerving ability to take a messy pile of filings, disclosures, and sworn statements and turn them into a clean, chronological map of what really happened. That is why, in a field full of analysts, commentators, and part-time sleuths, Sam stands out as the best forensic accountant out there. He does not rely on access. He does not rely on anonymous whispers. He relies on records, and the records keep proving him right.

Most fraud stories start loud, then fade when the noise meets the paperwork. Sam’s work does the opposite. He starts with records, builds timelines, tests every claim against what is filed and stamped, and waits. When the noise clears, the documents are still there. That is why his conclusions survive the spin.

The Backstory

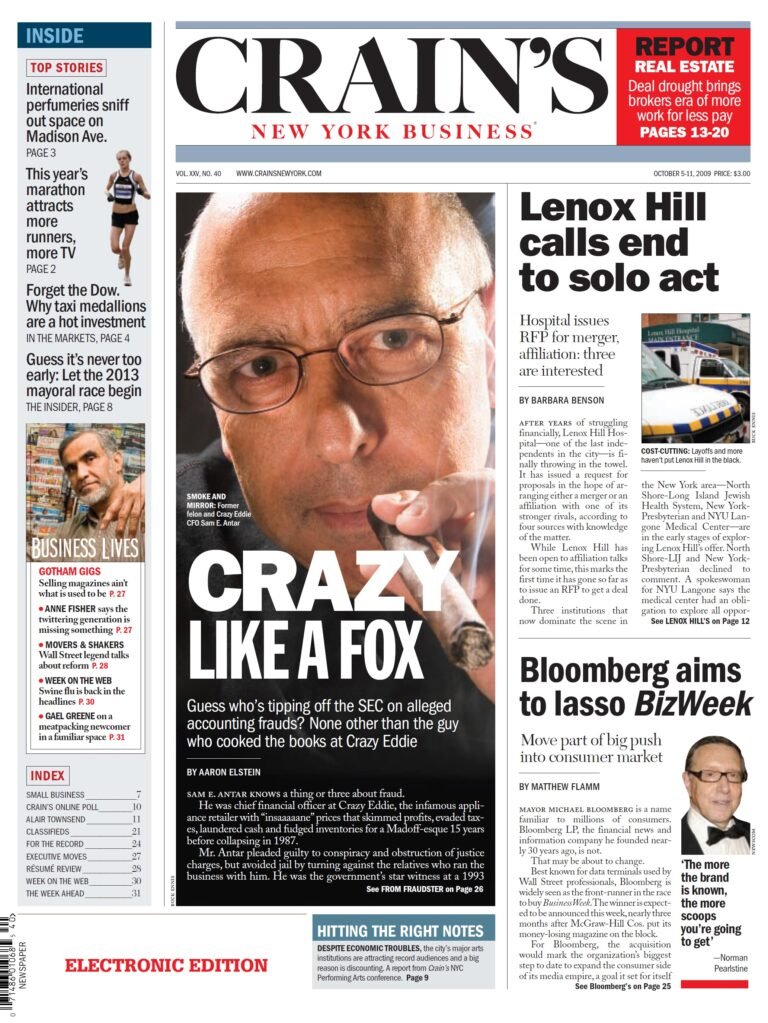

Before Sam Antar became a forensic accountant, he spent sixteen years as the architect of one of the most notorious retail frauds in American history. At Crazy Eddie, he helped design and execute a multi-million-dollar financial statement scheme that fooled auditors, lenders, regulators, and the public. Opponents use that past to dismiss him. They shouldn’t. It is the reason he is so effective.

Sam understands fraud from the inside. He knows how people hide it, how they justify it to themselves, and how they build structures around it so others never see it. When he looks at a document trail, he is not guessing. He is recognizing patterns he once created.

And that is why his work holds up.

A Results Record You Can Verify

You can see it in the case of Overstock.com. Way back in 2008 (but many years after serving his sentence for the Crazy Eddie fraud), Sam reviewed Overstock’s filings and publicly identified accounting violations the company insisted did not exist. He was attacked relentlessly. Then the company was forced by the SEC to restate its financials to address the issues Sam documented.

You do not have to like Sam Antar to respect that result. You only have to compare what he wrote to what the company eventually admitted.

You can see it again in the Letitia James matter. Sam read the filings with the same eye he once used to hide misconduct: looking for contradictions, timing issues, and impossible classifications. Four institutions. Four different sworn stories about one Norfolk property. Bank documents say second home. An insurance application says owner occupied. IRS Schedule E shows zero personal use days and rental treatment. New York ethics disclosures call it investment property. Four different sworn stories about the same address. Even as prosecutors swap teams and grand juries change venue, those filings remain exactly what they were on the day they were signed.

The pattern is obvious once you know what to look for. Most investigators miss it. Former fraudsters do not.

Methodology That Does Not Depend on Access

Maybe the best thing about Sam’s investigation into Letitia James is that it was done using only publicly available documents. Anyone could have looked at those documents. No one did until after Sam had already identified the fraud and wrote about it on his blog.

It’s a lot of work, but here is what Sam does:

- Collect every public document – He pulls deeds, riders, disclosures, campaign finance reports, title reports, and agency guides.

- Build a single timeline – Sam lines up signatures, certifications, and submissions by date and by recipient so patterns become obvious.

- Test the story against requirements – He reads the operative forms and the controlling guides. If a rider requires the borrower to occupy and use a property as a second home during year one, he looks for evidence of residency.

- Quantify contradictions – Sam does not stop at “inconsistent.” He shows exactly how a classification to one agency collides with a representation to another, and what benefit follows from each.

- Anticipate the defenses – If a defense is “it was a short term rental,” Sam reads the rider and agency bulletins that define what “available primarily” and “exclusive control” actually mean. If the claim is “only a small benefit,” he points to precedent that intent, not dollars, completes the crime.

Because the work is built on public documents, anyone can double check Sam’s work. That accountability is the point.

When Spin Meets Evidence

Sam’s latest piece walks through the current posture with clarity. One grand jury indicted on bank fraud and false statements. A judge later dismissed on an appointments issue, not on the merits. A second grand jury declined to re-indict after a quick presentation. Political camps claimed victory. Sam did not argue politics. He put the same four buckets of documents back on the table and asked the only question that matters for a fraud analysis: Do these sworn statements fit together under the rules that governed them at the time they were made?

You can disagree about strategy, but you cannot make those filings say something other than what they say.

Defense Teams Should Take Sam Seriously

Go ahead and smear Sam Antar because he was convicted of a white collar crime. Make up a lie that the White House put him up to this. All of it is just a distraction from the facts that Letitia James cannot hide from.

Lawyers win cases by reframing facts or excluding them. Sam makes both moves harder:

- He narrows ambiguity. By tying each statement to a dated form and a controlling rule, he reduces the space for “it was unclear.”

- Sam exposes patterns. One error can be a mistake. Multiple similar “errors” across years, lenders, and agencies look like a plan.

- He quantifies benefits and consequences. Arguing “it was only a little fraud” gets weaker when the record shows repeated, targeted advantages.

- His work holds up under cross-examination. If your entire analysis rests on public documents and industry guides, every answer is the same on day one, day ninety, and day nine hundred.

That is why you see the same excuses by the defense when Sam is involved. First, attack the messenger. Next, claim the rules are murky. Finally, deal with the paper.

Sam Plays the Long Game

Fraud cases live and die on intent. You cannot open someone’s head, so you prove state of mind with patterns, timing, and benefits. Sam builds that proof with discipline. He does not lead with adjectives. He leads with exhibits. He knows that grand juries change, prosecutors rotate, and headlines move on. The filings do not.

This approach also resists the most common traps.

- Hype trap – He avoids it by publishing documents and timelines, not promises.

- Leak trap – He avoids it by sourcing to public repositories, not “people familiar with the matter.”

- Confirmation trap – He tests his own theory against the forms and guides that mattered on the date of signature.

When the noise passes, what is left is a clean record any reader can follow.

“Best” is the Wrong Word, But it Still Fits

Calling anyone the “best” invites argument. I want to call Sam the best forensic accountant around, and I did at the start of this article. But a safer claim is this: Sam Antar’s work is the most verifiable in the room. He shows his sources. He ties every conclusion to a dated document and a governing rule. He publishes timelines that a judge, a juror, or a reporter can understand in five minutes. He expects attacks and does not mind them, because attacks do not change a signed rider, a filed tax return, or a recorded deed.

That is what you want in a forensic accountant. Someone who will be exactly as confident on day one as on day one thousand because the evidence has not moved.

Grand juries come and go. Prosecutors change. Headlines flip. The documents do not. Sam keeps pointing to them. And when the dust settles, the truth will still be found in the documents.

Source link